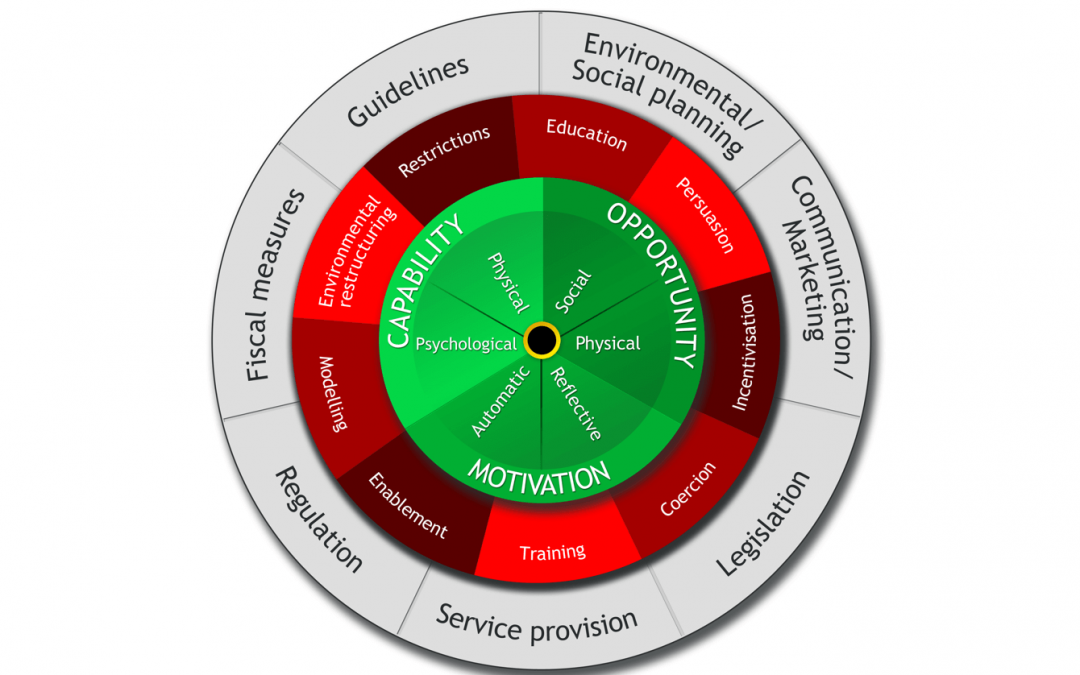

Illustration: The Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al Silverback Publishing)

If your job includes helping people make positive changes to how they eat, you’ll know how hard this can be. Helping people lose weight is complex. There is no end of advice and new wonder diets that promise incredible results, but these don’t tend to seriously address the likelihood of weight re-gain. However you lose weight, if you return to how you were eating before, you’re likely to regain the weight lost. So to maintain your weight loss, you need to change your eating habits. And that is easier said than done.

In this newsletter I’m going to tell you about new research on behaviour change, which you can integrate into your own work, to help your clients achieve success.

So make yourself a cup of tea and give yourself ten minutes to read and digest this.

Losing weight and keeping it off means changing habits

Behaviour change is one of the central elements of changing what we weigh. It’s not the only one of course. As the British Psychological Society (BPS)’s recent report, “Psychological perspectives on obesity” says, biological, psychological and environmental factors all contribute to gaining weight and struggling to lose it, and that is true whether you develop obesity or not. The balance of different factors differs between individuals, so some people have much higher biological predisposition to weight gain or the development of metabolic disease.

If your client needs medical or surgical treatment for obesity, behaviour change will only be part of the overall treatment. But it will be an important part. For more information on incorporating behavioural change into surgical treatment, Dr Denise Ratcliffe’s book “Living with Bariatric Surgery” describes how to incorporate behavioural changes to minimise weight regain.

Other clients may need to focus just on behaviour change. What I tell clients who come to see me for help with losing weight who do not have obesity is this: If you want to lose weight, you need to change your eating habits. If you want to lose weight permanently, you need to change your eating habits permanently

Achieving behaviour change is not the same for everyone.

Our genes and our environment both play a significant role in how the appetite system in our brain functions. This means that how easy or difficult it is to change how we eat, varies between individuals. If Andrew has been under chronic stress for years, his appetite regulation system will operate differently than that of Ben, who has been fortunate to have experienced only occasional stress. And they’ll both be different from Cameron who has a strong family history of metabolic disease.

Changing the eating habits of a lifetime overnight is just about as hard as you can get!

Conventional diets tend to offer a scattergun approach to weight loss: offer a list of rules to eat by, and the weight will come off. But often those rules are vastly different from how any of us usually eats, and following the diet means making numerous changes to our established eating habits, all at once. It is hard enough to make a single change, so making multiple changes all at once is asking for trouble. As the BPS report says,

“People and populations can change their behaviour, but it is not a simple process.”

How should we approach helping people change unhelpful behaviours?

Put simply, we need to help people to start where they are now, identify which of their current eating habits are contributing to keeping them overweight, and then work with them one step at a time to make changes. As Michie and colleagues from University College London say in their book “The Behaviour Change Wheel”, limiting your intervention to just one or two specific behaviours in the first place – introducing change incrementally and building on small successes – can be more effective than trying to do too much too quickly.

Here’s a short video I made on the importance of stepwise habit change.

In “The Behaviour Change Wheel”, Professor Susan Michie, Dr Lou Atkins and Professor Robert West have developed a comprehensive way to design ways of helping people change unhelpful behaviours. What they manage to do is cover interventions aimed at individuals and at organisations or nationwide health initiatives. Impressive. If you’re involved in designing and delivering population-scale interventions, or organisation-wide behaviour change, this is the book for you. But it’s also useful for those of us concerned with helping one individual at a time change their own unique set of unhelpful habits. It’s not possible to summarise the whole approach in a few paragraphs, so I’ll just pull out a few key points.

Analyse the behaviour

The Behaviour Change Wheel emphasises the value of analysing the behaviour you want to change and taking into account all the relevant aspects of the behaviour you’re targeting –

- thinking about the size of impact changing this behaviour will have on the person’s life

- gauging how easy it will be for the person to change the behaviour

- considering how central this behaviour is to the overall pattern of unhelpful behaviours. For example, learning to stop eating at the point of being just full can be the basis for stopping several types of over-eating whilst stopping eating biscuits with coffee might not have any generalizable effects.

Specify the behaviour exactly

Michie and colleagues emphasise how useful it is to specify the behaviour exactly, and the context in which it occurs. And then they consider what must come together for the client to put into action the new, helpful behaviour:

- Capability (physical capacity, knowledge, skills etc)

- Opportunity (affordable, physically accessible, enough time to do it)

- Motivation (the desire to do the new behaviour rather than not do it, or the desire to do the new behaviour rather than another unhelpful competing behaviour).

This “COM-B” model (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) stresses that interventions must affect one of more of these components in order to change established behavioural patterns. To take the example of someone changing to smaller food portions… whilst Opportunity might be enhanced by increased availability of portion-controlled products or smaller crockery and utensils, Capability may be increased by educating the person about the amount of food they need at each meal to enable their weight to reduce, and Motivation by strengthening their awareness of the benefits of reaching their goal.

The COM-B model makes the important distinction between conscious and unconscious aspects of motivation. Conscious motivation involves making plans or deliberate intentions (e.g. wanting to lose a stone in weight), whilst unconscious motivation involves automatic processes such as wants, needs and impulses (such as the urge to eat something tasty). I’ll talk about Motivation in a future Appetite Retraining Professionals’ Newsletter as it is an important and complex topic.

If you’re interested in becoming a real behaviour change nerd, Michie and colleagues have done the astonishing job of creating a standardised language for describing the active ingredients in behaviour change. They identified 93 (you read that right!) Behaviour Change Techniques under 16 different headings (p148 of the book) from behavioural experiments to reframing.

Unhelpful Eating Habits Checklist

In developing Appetite Retraining, the same unhelpful eating habits were coming up time and again with clients, so I assembled them into my “Unhelpful Eating Habits Checklist”. As you can see, the unhelpful habits fell into four groups:

- Lack of eating routine

- Eating too much at a time

- Eating when not hungry

- Problems with what you eat or drink

This list gives you a way of helping your client identify specifically which habits they may need to change, and once they’ve done this you can talk with them about which habit they’d like to tackle first.

What are the limitations of focusing on behaviour change?

Eating is complex. Eating meets a range of social and psychological needs, and for some people strategies to support weight loss and maintenance need to go beyond simply promoting new healthy behaviours. For many of us, over-eating has developed as a way to regulate emotions and cope with emotional distress. Emotional eating will be the subject of a future blog. This important topic is often talked about in the media as though it is one thing, but it’s not.

Another potential obstacle to successful behaviour change is self-sabotage. This is something I’ve studied in people I’ve worked with, and I identified 4 types of saboteur that come up often. These are lack of willpower, lack of motivation, lack of self-belief and pressure from others around eating. I’ll be writing about each of these in future articles.

How you can start using behaviour change research in your clinical practice

I’d suggest that you start with my Unhelpful Eating Habits Checklist. Ask your client what they most want to work on first, and consider encouraging them to stick to one or two changes to begin with, so they experience success quite quickly. The weight change might not be as dramatic as a radical diet, but it will be sustainable if the focus is on changing habits. If you’re a dietitian or nutritionist, you may be focusing on particular changes to the balance of what foods your client eats. In that case the UEH checklist offers a way of introducing a discussion about stepwise change. You can still use the principles of the Behaviour Change Wheel, and tailor them to the changes your client is aiming to make.

More support to help you help your clients lose weight

I hope this helps. Do let me know how you get on. Future topics I’ll be exploring include visualisation, emotional regulation and habit change, so get in touch if you have any questions about these.

Further information and training for you

If you’d like to attend one of my training workshops for Professionals, details of upcoming events are here.

To sign up to receive the Appetite Retraining Professionals’ Newsletter regularly, visit this page on my website and enter your details. I write one article a month for professionals and one article a month for the general Appetite Retraining Newsletter, and I’d love you to join me.

See you next month

Best wishes

Dr Helen McCarthy

Further Reading

British Psychological Society (2019) Psychological perspectives on obesity: Addressing policy, practice and research priorities.

McCarthy, H (2019) How to Retrain Your Appetite: Lose weight eating all your favourite foods. Collins and Brown

Michie et al (2014) The Behaviour Change Wheel: A guide to designing interventions, Silverback Publishing

Ratcliffe, D (2018) Living with Bariatric Surgery: Managing you mind and your weight Routledge